On Tuesday 27 July 2021, I was delighted to address the Rotary Club of Western Endeavour in Leederville. I’d been asked to speak following my article on the flawed underlying assumption that informs so much of our welfare policy. This is the speech I gave.

Thank you for the invitation to present, it’s a delight to be here. I’d like to add my acknowledgment the traditional custodians of the land I am standing on, the Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation. I pay my respects to their elders, past present and emerging.

Today is about getting you thinking, so I hope you’re ready to engage your grey matter after that delicious breakfast. You’re going to be thinking about how we could move Australia from being lucky to smart, in the financial sense.

Most speeches I give are about individual financial capability and helping people to do the best they can with the resources they have. Today however, I’m very happy to be asking you to focus your attention on systemic options instead – the big levers available to a country as lucky as ours.

We’ve all heard that phrase, the lucky country. It was not coined in praise, or about being grateful. It was pointing out that we won the country equivalent of the ovarian lottery because we have lots of resources, and to quote the author Donald Horne, our home is “run mainly by second rate people who share its luck”.

Basically, we’ve landed with our bums in the butter. We don’t have to work as hard as other countries to be prosperous. We don’t face the same obstacles other countries do, like overpopulation, or at least not to the same extent as others. Even COVID’s largely passed us by so far.

That’s probably why ‘she’ll be right’ is a catch-cry. She often is right. Usually, luck’s been a major factor, sometimes more so than hard work or good planning. It’s not often because we’ve been particularly smart in our approach.

The thing is, she isn’t right in one important area.

Poverty is a massive problem in Australia

…and it’s getting worse, not better.

One in seven Australian adults lives below the poverty line.

One in six Australian children does too.

Over 116,000 Australians slept rough last night, and hundreds of thousands – possibly millions – more slept in their cars, or on couches, or in the spare room at a friend’s, or in caravans, because they don’t have housing security.

The age and gender group experiencing the fastest growing demand for homelessness support in the last few years has been women over 55.

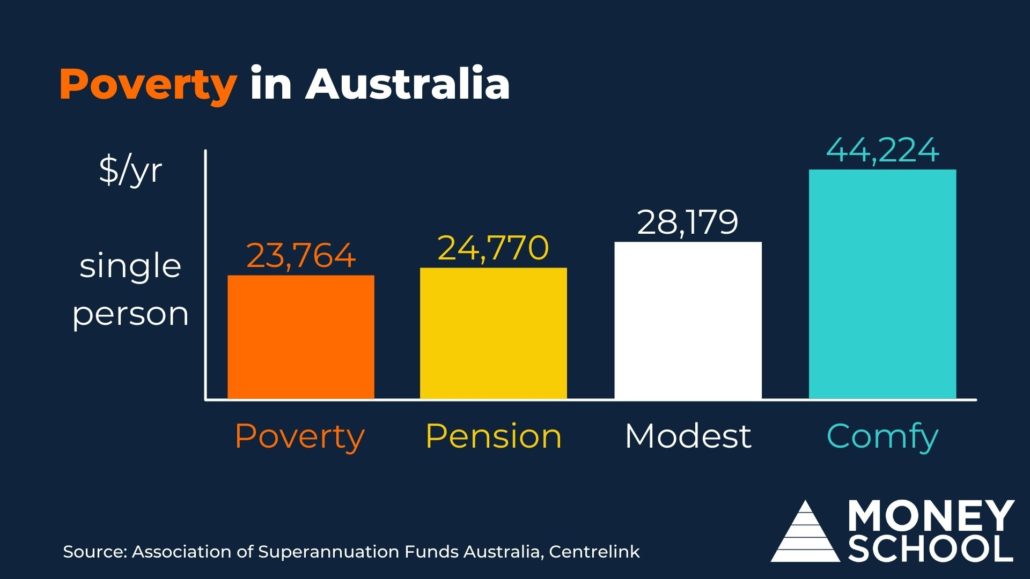

Then there’s the pensioners living on the poverty line itself – paying taxes all their lives and ending up with a subsistence level of support.

We have to get to the root of what causes poverty, because no one should have to live that way in a country as wealthy as ours. We need some serious introspection, because I believe the majority of Australians have inherited incorrect assumptions about what causes poverty.

Think back to your childhood. Did anyone ever tell you not to give homeless people money because they’ll just buy alcohol or drugs with it? Maybe it was a specific case, someone you walked past them on the street. Maybe it was in general, about not encouraging people to be dole bludgers by giving them more.

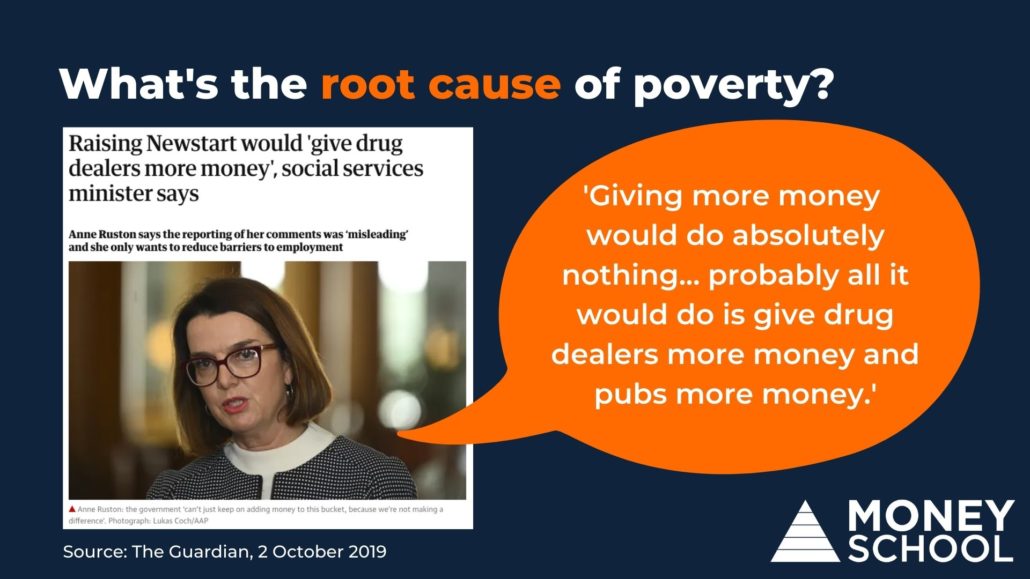

It’s a common phenomenon, and not just historically.

In 2019, Social Services Minister the Honourable Anne Ruston was quoted regarding what was Newstart (and is now JobSeeker): “Giving more money would do absolutely nothing … probably all it would do is give drug dealers more money and give pubs more money.”

Politically, that’s a typical Liberal sentiment. As a member of a Liberal voting family, that’s certainly how I was raised. I heard, over and over:

“You don’t give poor people money, they’ll just waste it.”

The inference? Poor people are the root cause.

It’s a character flaw.

For a long time, I believed it. It was reinforced by what I saw, such as on the show Struggle Street. I feel like I spent a lot of the watching time alternately cringing, and yelling pointlessly at the TV: don’t buy that!

In Series 1, Ashley (shown here with his family) showed some enterprising spirit when he collected scrap metal and took it to get some cash. I was super impressed, until he spent $20 of the nearly $50 he’d made on sandwiches from the servo. That could have fed his family twice over.

In Series 2, Michael lives in transitional housing and will be homeless if he can’t make his $100 a week rent. After a couple of challenges, he gets approval to access his $3,500 in his super to get ahead. He spends over $2k on an electric guitar.

These behaviours reinforced that message I’d absorbed, that poor people make bad financial choices.

Then I came across some fascinating research out of Princeton University in 2013. They tested people’s IQ in response to financial stress. Their study found evidence of what’s known as poverty brain. Specifically, if you’re experiencing financial stress, your IQ will drop 13 points.

And yes, I mean you. I mean all of us. Even Albert Einstein would have been 13 IQ points dumber if he felt like he might lose the roof over his head or not be able to eat for want of money.

The level of financial impact it takes to induce that stress is different for each of us, but when we reach that point, the impact will be the same: we’ll be dumber. The impact is as bad as going for 24 hours without sleep, or being intoxicated. And that’s just on average – extreme financial stress can have an even bigger impact. Up to 40 points apparently.

When you’re dumber, you’ll make more mistakes. You’ll make worse choices.

Poor people don’t make bad choices. People make bad choices when they are poor.

When you’re on the bones of your bum, losing a $20 note out of your wallet can be enough to put you right into that financial stress mode. Those of us in more comfortable situations might be mildly irritated by such a loss, but it wouldn’t change our IQ. For someone living in poverty, it does.

Expecting someone to dig themselves out of poverty is like tying a brick to each of their ankles, throwing them off a jetty and telling them that if they really wanted it and were willing to work, they’d swim their way to safety.

Some might make it, but many won’t.

The ‘poor people make bad choices’ believers will tell you those who drowned did so because they didn’t want it bad enough, weren’t willing to put in the hard work, that they were undeserving. They’ll laud the people who manage the swim, applauding their internal fortitude. We love a rags-to-riches story.

Sadly, they’ll be wrong. Correlation and causation aren’t the same thing. In this case, we’ve confused the symptom with the cause – and getting it arse-about is why we don’t seem to be improving.

Poverty is not a lack of character, it’s a lack of money.

When you treat poverty as an outcome instead of a character flaw, you can test the most obvious solution: giving poor people more money.

Good news: those tests have been done extensively in countries all around the world. They’re happening right now, and we’ve even had our own taste of it in 2020 thanks to JobKeeper and JobSeeker.

I’m talking about universal basic income, UBI for short.

If you’re curious about the experiments and their outcomes, I have two books to recommend:

- Utopia for Realists, by Rutger Bregman (who also has an excellent TED talk)

- Reset, by Professor Ross Garnaut

The premise of UBI is: give people money for free.

With no strings attached. Not on the condition of working, or providing a clean drug test, or not having been imprisoned at any time in the past. Just, give it to them.

By taking away the ‘poor’ factor, helping them feel like their housing is secure and they’ll be able to eat, you take away some of the stress that leads to poverty brain.

We’ll still have drug addicts, alcoholics, domestic abuse and bludgers. But we’ll have far fewer of them, and those tendencies have never been confined to income brackets anyway. They start with trauma that can’t be averted simply by earning a good wage.

Is UBI a silver bullet?

No. We still need people to learn how to manage their money wisely, to save and invest for their future. Individuals must still take responsibility for how they use their cash. But I can’t teach someone in poverty how to manage their money with a straight face when they have to choose between eating and paying rent. Don’t offer to teach someone who’s drowning to swim – throw them a life ring, get them safe. Teaching them to swim can come later.

But UBI might be the simplest, most direct, and most equitable lever we can pull to lift our people above the poverty line.

I’d like us to test UBI, here in Western Australia. We have the cash to do a comprehensive experiment for a few years, and we should. Imagine – we could say WA stood for Way Ahead instead of Wait Awhile!

If we can manage that, the work I do through Money School and organisations like it can reach the people who really need it. We can help people become financially capable: saving, buying assets and avoiding bad debt. And I do mean capability, not literacy: literacy means ‘I know’, capability means ‘I do’. It’s not enough to know the theory – you have to apply it. You have to treat the money you earned as a precious resource not to be wasted – because you trade your time to earn it, and those seconds, minutes and hours you spend at work are non-renewable.

We can have the world’s best financial literacy programs and curriculum and we still won’t fix poverty. Poverty is a lack of money, not a lack of character or literacy. Until we get that root cause sorted, we’re pushing the proverbial up an inclined slope.

Thank you for allowing me to wax lyrical on this topic. I hope it’s given you some new information, or at least got you thinking.