The phrase ‘Do your own research’ (DYOR) is getting a workout on all kinds of topics these days.

But what does DYOR really mean, especially in the context of personal finance?

(Don’t panic, we’re not going anywhere near the vax debate here – but I am going to explain this thoroughly, so grab a beverage…)

DYOR means: ‘Don’t blame me if I’m wrong.’

It’s like a real life Get out of Jail Free card from Monopoly.

You put content out, tack DYOR on the end, and that (apparently) absolves the content creator of responsibility.

Whenever you see DYOR, try mentally substituting in:

- I’m not responsible for your decision even if I’m suggesting you make it in this piece of content,

- I’m not accountable for any loss you incur as a result of following my advice, or

- Follow my advice at your own risk.

Because that’s what it means.

Why?

Because doing one’s own research is ridiculously impractical in the everyday sense. I don’t know anyone who actually does their own research – myself included.

Research takes years, if not decades, to do well.

…and that’s not a decade in which you randomly read a few articles an algorithm suggests for you each year.

It’s a decade of single-minded focus, for thousands of hours each year, and with lots of checks and balances built in – like tests for bias, sample size, methodology and peer review before publication.

If we all did our own research, it would take several years to reach a conclusion on anything.

We’d all be running around in lab coats, learning how stats work and designing experiments, with no time for another day job. What a waste of enormous amounts of time and energy that could be better spent elsewhere.

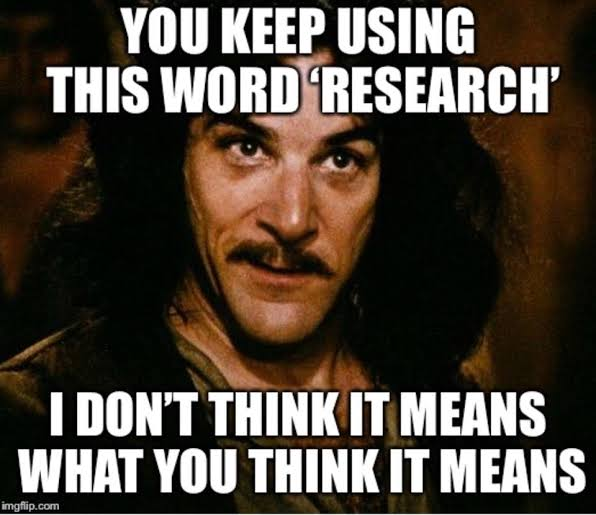

When used in DYOR, ‘research’ has become code for consuming content, for example reading articles, listening to podcasts and radio, watching TV and YouTube clips.

But don’t fool yourself.

When you’re consuming content, you’re not doing research.

You’re reading, watching or listening. Perhaps widely, perhaps applying critical thinking to what you see and hear …but it’s not research.

Mostly, that content is not:

- randomly selected – it’s been served up to you by an algorithm that preferences clicks and outrage, not scientific methods or accuracy.

- screened for bias – it’s rarely had any checks on whether the source data or content itself has inherent assumptions that render its conclusions less valid.

- based on statistically valid methods – so often such articles are handfuls of anecdotes pieced together rather than comprehensive testing.

- peer-reviewed – it’s had no critical analysis, probing or stress-testing from suitably qualified peers who can confirm the methods and conclusions are sound.

In personal finance, there’s also one humungous issue with a lot of such content:

It doesn’t declare how it makes money for its creators.

The industry is full of people selling financial products and services – their own, or someone else’s – that produce ‘educational’ content that (surprise, surprise) leads to suggesting purchase of said products and services.

Which I’m totally OK with – if it’s declared.

It often isn’t.

My favourite example is school banking, which ASIC reported on last year, finding:

‘School banking program providers fail to effectively disclose that a strategic objective of these programs is customer acquisition.’

In other words, the banks get paid by the ongoing loyalty of the customers they acquire, through bank fees and interest payments.

If one of the largest companies in Australia can get away with it for 90+ years, imagine what everyone else is doing.

But if DYOR isn’t practical, what can you do instead?

Critically assess educational content you consume.

Specifically:

1. Ask how the source gets paid.

Commissions create conflict of interest. No personal declaration of good intent can fix a system that’s flawed by design.

Find out:

- Are they paid by advertisers, so their financial success is based on the number of viewers?

- Do they get a commission, so they have reason to persuade you to buy something?

- Are they financed or sponsored by a particular company or lobby group?

- Even if they seem agnostic, are they a ‘pay to play’ platform showing only part of the market’s competitors?

If your source will financially benefit from your decision, that’s a good sign you need to get independent verification or advice.

2. Read, watch and listen widely

Search engines and social media platforms are, by definition, echo chambers.

If you’ve clicked on something before, you’re more likely to click on something similar, and that’s how Google and Facebook (and all the rest) get paid. They play on our innate confirmation bias.

Don’t fall into the trap of believing your own stories just because what you’ve seen reinforces them.

For example, I follow many outlets and people I consider idiotic so the algorithms deliver content that isn’t quite so one-sided.

I engage in debate with people whose views I find borderline offensive, just in case they have something useful to say or a side I haven’t considered. Sometimes they do. Sometimes they’re simply unable to let go of an obviously wrong idea, in which case – more fool them. I jog on.

Listening to them doesn’t mean I agree with them. It doesn’t even mean I believe their point of view is valid. As Patrick Stokes so eloquently explains in this excellent article on The Conversation:

‘No, you’re not entitled to your opinion. You are only entitled to the opinion you can argue for.‘

So, argue.

Put the ideas you have about personal finance under the microscope.

As Tim Minchin says:

‘Be hard on your beliefs. Take them out onto the verandah and beat them with a cricket bat…’

You’ll have a better chance of making financial decisions that work for you, and you’ll be less likely to fall for a con-job.

And here’s to the researchers (in the traditional sense of the word) who’ve done the hard yakka so we don’t have to. Thank you!