By Lacey Filipich BEng(Hons) MAICD

The 2015 Intergenerational Report (‘The Report’) was published on 5 March 2015. It’s a predictive exercise: based on today, where will we (Australia) be in 40 years? Assumptions abound and of course you can spend a lot of time on whether those assumptions are reasonable or not, but it’s far more interesting to consider the implications for those of us who still plan to be around in 2055. So what did The Report find?

Findings of interest for those interested in money

The following figures are based on Commonwealth of Australia data, taken from the 2015 Intergenerational Report.

1. We will live longer, healthier lives

A child born in 2015 can expect to live to their early 90’s whereas a child born 40 years later may expect to live to their mid 90’s. More specifically, life expectancy predictions are:

Year | Male | Female |

2015 | 91.5 | 93.6 |

2055 | 95.1 | 96.6 |

The increase is all ‘disability free’ years, i.e. we will be healthier for longer. The government probably thinks ‘Yay, this means you can all work longer!’ I lean towards ‘Yay! We can have more fun in our end-of-working-life retirement!’

2. Our population is aging

No sh*t, Sherlock. Yes, we’ve all heard about our aging population, which is the inevitable result of longer, healthier lives and stable birth and death rates. But by how much will the age distribution change?

The most interesting ratio (in my humble opinion) is the number of people of working age (15 – 64 years) vs. those of retirement age (65 or older). Why is this of interest? Because the workers provide for the retirees. Their taxes fund pensions and health care, two of the greatest costs of an aging population.

In 2015, the ratio is 4.5 – that is, 4.5 workers fund 1 retiree.

In 2055, the ratio is expected to drop to 2.7 – that is, 2.7 workers fund 1 retiree. That’s a 40% reduction.

3. Growth will slow (slightly)

We measure growth via real Gross Domestic Product (GDP). A quick economics lesson, for those wondering:

- ‘Real’ means inflation has been taken out. Using real dollars means we’re comparing apples with apples when comparing financial figures across decades. As a rule, real is much more useful than nominal (which includes inflation) unless you’re talking about inflation.

- GDP is how much we produce in a year as a country – the sum of all our efforts.

- Over time, we add value through our blood, sweat and tears. This is what growth in our GDP represents.

From 1975 to 2015, we have had 3.1% annual growth in real GDP. This includes an ‘unprecedented 23 year stretch of unbroken economic growth that is continuing.’ Why is that important? Because it is usual to have some years where growth slows – that’s the natural economic cycle. It means we’ve largely dodged the impact of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)… so far anyway.

Over the next 40 years, real GDP growth is expected to be slightly lower on average at 2.8% per annum.

4. Debt will grow

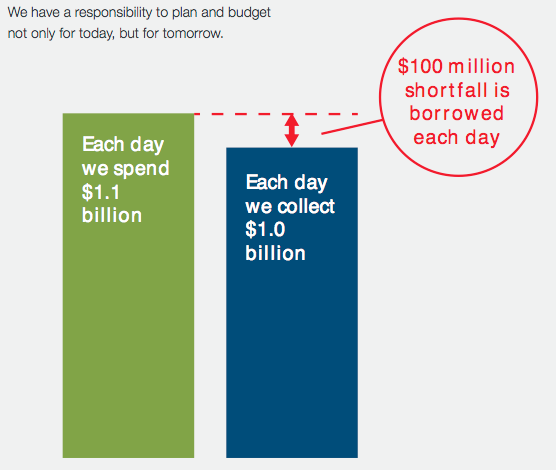

I think this is my favourite image from The Report, and it needs no explanation:

Explanations don’t get much simpler than this. We’re living beyond our means. We are borrowing $100 million every day to subsidise the lifestyles to which we’ve become accustomed. Over a year, that’s $36 billion we’re borrowing. Gross debt is currently around $360 billion (22% of GDP) so that’s an increase of 10% in the next year if nothing changes.

What does this mean for Australia as a whole?

The implications of the findings are:

- We can expect to spend more on health care and pensions (at the very least) as our citizens will live longer.

- The burden of this increase will fall on fewer people as our proportion of working to retired citizens drops.

- Debt is rising at a rate that will eventually overtake income (GDP) growth unless we make significant changes.

That third point will be of great concern to politicians (and should be to citizens as well) because it’s unsustainable. Eventually debt will overcome earnings, and what would happen to an individual in that circumstance? They’d go bankrupt. Aside from the obvious, why would this worry the politicians? Because they will eventually have to do something unpopular – like raising taxes or cutting spending. These moves do not win votes; hence no one wants to do them.

What does this mean for individual Australians?

This report can and should have an impact on your financial planning. How so, you ask?

1. Longer retirements

After you retire permanently, your lifestyle will be funded by the pension and your superannuation; in whatever combination those apply to you. If you retire at 65 and live to 95, you’ll have 30 years of life with no working income. That’s a long time, and you’ll need a big nest egg to sustain you for that duration. This is, of course, the average case. You might only have 10 or 20 years to finance… but maybe you’ll have 40. The worst scenario is that you run out of money before you die, because living on the pension is hard. It’s around $20,000 per annum – that’s below the poverty line, even if you own your own home outright. That’s assuming we’ll still have a pension!

2. Less ‘government subsidised’

Barring a phenomenal shift in our technology or some other miraculous discovery that raises our income, we can expect tax increases and/or government spending cuts in the future – hopefully not too distant either, as without these the national debt will eventually become unmanageable. So you’ll either be handing over more of your pay, or you’ll have less tax concessions (e.g. negative gearing might go), or you’ll have a lower rate of funding on public services like Medicare. No matter how it’s enacted, the effect on most people of working age will be less money in their pocket.

3. Lower returns

Less money in pockets = economic slow down.

Economic slow down = asset values and returns drop.

The GFC was a painful reminder of this, as legions of the newly retired found themselves back on the job market to make up for the sharp decline in their superannuation value and payments. We have not yet completed the great deleveraging the long-term debt cycle calls for and it may well be in the post.

The bottom line: you can’t rely on a 10% return on investments every year. You might not even be able to expect a 7% return. This means you need a lot more equity behind you when you plan to retire… unless you’re happy to take a cut in lifestyle.

If this was gobbledygook to you, I highly recommend you watch Ray Dalio’s 30 minute animation on ‘Economic Principles – How the Economic Machine Works’. Actually, watch it regardless of whether this made sense to you – it’s a succinct, clear explanation of how debt works and its effect on our economy.

What can you do about it?

If you’re like me, you might prefer take matters into your own hands rather than wait for the government to look after you. Consider these suggestions:

1. Work out your needs

I’m referring to a long-term plan here.

Firstly, what lifestyle do you want – now and when you retire? How much does that lifestyle cost? Is it $30K a year, $50K a year, $150K a year? The amount you need – and want – will directly influence your financial strategy for the next several decades. You need to know your target because you need to know how much you need to accumulate in order to finance your chosen lifestyle.

Once you know how much you want to spend each year, you need to work out how long you want to be retired for. Are you planning to retire at 65? Better plan on financing 30 years or more. How about those who aspire to retire at 50? You’ll probably need enough to get you through 45 years.

Finally, think about the next generation. Is your aim to leave behind most of your asset balance for your family to enjoy, as a bequest to them? Or are you happy to consume some or all of your assets as you go through your retirement, leaving them to sort themselves out?

Now you have three numbers:

- Target annual income.

- Duration it has to last.

- Your target final asset balance.

With this, plus one assumption about yield (a big assumption, I grant you) you can calculate the asset value you need before you retire.

Let’s take a simple case to calculate:

- You want $100,000 a year to live on when you retire (ignoring tax implications)

- You estimate you’ll get 5% returns on your capital (reasonably conservative)

- You think you’ll have 30 years of retirement as you’ll retire at 65 and expect to reach 95

If you want to preserve all your capital – that is you just want to live off the yield of your assets – you’ll need $100,000 / 5%, which is $2 million in capital assets. In this scenario, you can theoretically go on supporting yourself forever at the same rate because you probably won’t* draw down your asset balance.

If you’re happy to draw your asset balance down to $0 over the 30 years, you’ll need around $1.56m in capital assets.

* Note: Even if you achieve $2 million in capital assets, there are no guarantees that you won’t draw down your capital balance. 5% would be an average – some years will be higher, some lower, and some may even be negative. If lower or negative years happen early in your retirement, you’ll find your asset balance dropping quickly and you may not have anything to hand over to your kids and grandkids in the end anyway.

As an aside, consider your parents. As they age, they’ll need support. Will they have enough to keep them reasonably comfortable? Or will you have to include supporting them in your future plans? I mention this because it happened with my grandmother, and the result was my mother took her in cared for her for more than 12 months, with my mother covering the cost. It could happen to you…

2. Consider superannuation vs. your own portfolio

We refer to superannuation (super) most regularly in retirement planning because it’s compulsory. The government, recognising its eventual inability to support our aging population with pensions, made it so. You don’t miss your compulsory super because your employer pays it. It doesn’t come out of your wages, like tax does …unless you’re making voluntary contributions.

There’s no doubt super is good, but is it better than managing your own portfolio?

My simple answer is: no.

Superannuation is heavily controlled. You can’t access till retirement age without paying penalties, so early retirement is not incentivised. Most super funds have fees that eat away at your profits, so you don’t get the maximum potential return that you could if you managed your own investing. Also, laws around super can change. Tax exemptions may be removed or the tax rates may go up. It’s impossible to know exactly what the conditions to access your super will be when you retire, especially if that retirement is more than five years away. That’s a big risk.

The advantages of managing your own money are:

- No age restriction on when you can access the assets or their income, so you can retire if and when you want to.

- You don’t have to pay a fund manager – unless you want to. This can potentially save you fees.

The big risks are:

- You don’t save enough, because it’s not compulsory and it’s not managed by someone else (i.e. your employer and your fund manager).

- You don’t invest well, therefore costing you growth and potentially even making a big dent in your savings.

- You don’t keep track of your investments, so you miss big swings.

What’s the solution? If you’re five or more years away from your desired retirement age, I recommend:

- Stick to minimum required super contributions, choosing a fund with the lowest fees possible or possibly electing to manage your own super fund if you feel capable and your balance warrants it.

- Set aside additional savings – at least 10% of your net income, but better if it’s closer to 50%. The sooner you hit your needed asset balance, the sooner you can choose if and when you work.

- Learn how to invest those savings.

- Do it!

- Track your progress.

- Apply your investment knowledge to your super – change your asset mix when it’s appropriate, and keep seeking low-fee options.

3. Consider mini-retirements

This is off the strictly financial track, but I believe it’s perhaps the most important point.

We’re going to lead longer, healthier lives. And what are we going to do with all that life? Work more? I hope there’s something better in store than that.

The idea of working for 50 years straight gives me the creeps. No one died whispering the words ‘I wish I worked more.’ Stop thinking that you have to work, work, work and save, save, save constantly through the prime of your life so you can shuffle around a cruise ship in your 80’s. What a shame it would be to work hard all that time only to find when you retire you’re not able or interested in doing all the wonderful things you thought you would. What a waste!

There are many alternatives. Mini-retirements are one.

I am a shameless advocate for taking mini-retirements, which is the practice of taking extended breaks from working throughout your career. You effectively split your retirement years up and start enjoying them now while you’re still young and beautiful, as opposed to waiting till you’re old. I’m an advocate because I started doing it seven years ago and I haven’t looked back – it’s fabulous. I believe it’s done my asset balance and earning potential no harm either.

I won’t go into depth about mini-retirements here – that’s a subject for another post. But if you’re curious, check out this blog post from lifestyle design guru Tim Ferriss.

You can get more money but you cannot get more time – so make the most of it.

Where to from here?

We’d all love to be looked after by a caring and benevolent government, but I wouldn’t count on it. Far better to look after yourself. Any help the government then gives you is an added bonus! Use the outcomes of the Intergenerational Report as a timely kick-up-the-butt to take action:

- Work out your retirement needs:

- How much annual income do you want?

- When do you want to retire, and therefore how long must your assets support you?

- Do you want to leave any of your assets for your kids and grandkids?

- With these figures and your own yield assumption (I use 5%) calculate how much your asset value needs to be at retirement – contact Money School for a calculator if you need one.

- Based on the asset value you need, work out how you’re going to get there:

- Are you going to put more into super?

- Are you going to save more and invest it yourself?

- Learn about investing. Even if you stick with super, it will pay to understand how to choose a good investment – that way you can proactively manage your investment ‘mix’ through the choices offered by your super fund. If you’re managing your own money, this is practically compulsory. Money School can help you.

- Track your progress:

- How much equity do you have? (Remember equity is assets minus liabilities)

- Are you investments delivering the expected yields?

- Are you on track to meet your retirement target?

Got a comment? We’d love to read it. Please add your comments below or on the Facebook post.

What comes next?

Download our Free Financial Resources

Find the right Money School Course for you

Get the Book: Money School, Become Financially Independent and Reclaim Your Life, Lacey Filipich

Got a question: Contact Us

Lacey Filipich is the co-founder and director of Money School. She helps parents raise financially savvy kids and helps adults get on top of their finances. Connect with her on LinkedIn and follow the Money School Facebook page to learn more.

Very interesting article…it was like a kick in the backside, but really interesting nevertheless. It has cemented in my mind that I need help to sort my finances out because I clearly don’t know what I am doing. (I doubt my purse collection will keep me warm when I run out of money) Thanks for the butt kicking 🙂