As regular readers will already know: I am not a lawyer or a financial advisor. Nothing in this article about estate management should be taken as advice. It’s for sharing experiences only. Please seek local professional help to learn how any of it applies to your situation and jurisdiction.

Following Fran’s death, I’ve been her executor. It’s ignited my curiosity about wills and estates, along with wanting to protect my own family.

When you tell someone you’re an executor, all the horror stories come out of the woodwork.

It’s like when you’re pregnant the first time. For some reason, people want to tell you about their 36-hour labour, excruciating pain and panicking as they were wheeled into the operating theatre for an emergency C-section.

You hope you’ll be one of those who deliver your bub after just eight contractions with no painkillers (looking at my lovely friend L for that one!) …but you can’t help wondering what happened in the horror stories.

So I asked for more information about them.

What follows are four horror stories, of Jane, Lucy, Sam and Ben*. They were all affected by family members contesting estates. I am deeply grateful that they were willing to bare their souls on this blog. I hope it will be as useful for you, dear reader, as our previous similar story on bankruptcy.

(*names have been changed to protect the privacy of all involved.)

I’ve learned a lot from Jane, Lucy, Sam and Ben. I hope you will too.

I’ve been reminded

- why it pays to test every single assumption properly.

- estates can become a tool to wreak vengeance because you feel wronged during what should be a time of grief and healing.

- it’s a further reminder that a tool does not do evil in and of itself – you must look to the wielder of the tool for that.

I’ve also learned that paying for solid, specialist advice as early as you can is the best preventative going, so don’t skip the legal consult for creating your will and/or dealing with estates. A stitch, in time, can save nine – or hundreds of thousands of dollars as we’ll learn!

Keep in mind:

- There are still good people in the world. Not every family harbours money grubbing, embittered or vengeful members waiting to override the will of the deceased. Succession’s plot is not a prediction for all families.

- Most wills are not contested.

Also note that laws in Australia can be federal or by state/territory. Family law and superannuation law are federal. Estate law varies in each jurisdiction. So, decisions and legal advice regarding wills depends on what the local laws are, and how they relate to the federal laws. When seeking advice for your own estate or one you’re involved in, go local.

Before we launch in, let’s address the central issue that confuses most people new to the topic of estates:

Why are wills contestable?

Anyone who hasn’t dealt with a will says ‘But I thought that you had to follow a will? If it’s signed and notarised, don’t you have to do what the dead person wanted?’

You’d think so, wouldn’t you.

But that is not how it works if there’s an argument over what’s in the will in Australia. The deceased is, after all, deceased. It’s the living that are examined most closely, and their needs can be placed before the will of the dead person depending on circumstances.

There’s an excellent Insight episode on SBS called ‘Where there’s a will’. It’s worth the 53 minutes watch time if this topic fascinates you like it does me. It’s a repeat so I can’t guarantee it’ll still be there when you go looking.

In it, one of the professionals in the audience explains why wills can be contested…

Origins of challenging wills

Once upon a time, men owned everything. Women couldn’t even get their own bank accounts.

When a husband died, it was not unknown for them to bequeath their entire estate away from the family, for example to a hitherto unknown mistress, or to their alma mater so their legacy could be remembered with a building named for them. If followed, these wills would have left the widows and their children penniless.

The law had to include a provision for legitimate wives and children – who’d often been completely unaware of the contents of the will as they lovingly cared for the dying person – to be able to get some of that money so they could survive.

Over time, those laws have evolved, as have the definitions of what constitutes a marriage-like relationship. What we’re left with now is complex to say the least.

It reminds me of this quote on a different topic:

“There are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies, and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies. The first method is far more difficult.”

– C. A. R. Hoare

Substitute ‘law’ for ‘software design’ and assume we went for the less difficult path, and you’ve got a pretty accurate picture from what I’ve heard.

Which is why it takes so much legal time to decipher the many layers, and why no outcome is guaranteed in the courts – interpretation matters. Hence the saying: ‘The only winners are the lawyers.’

I suspect that’s why two of the four following cases have not gone to court, and the final one hasn’t got there yet (though it’s certainly heading that way, according to Ben). I guess at least the two no-litigation cases would end up in the ‘not contested’ pile, but they’re still not satisfactorily concluded for all involved so I wouldn’t call them ideal.

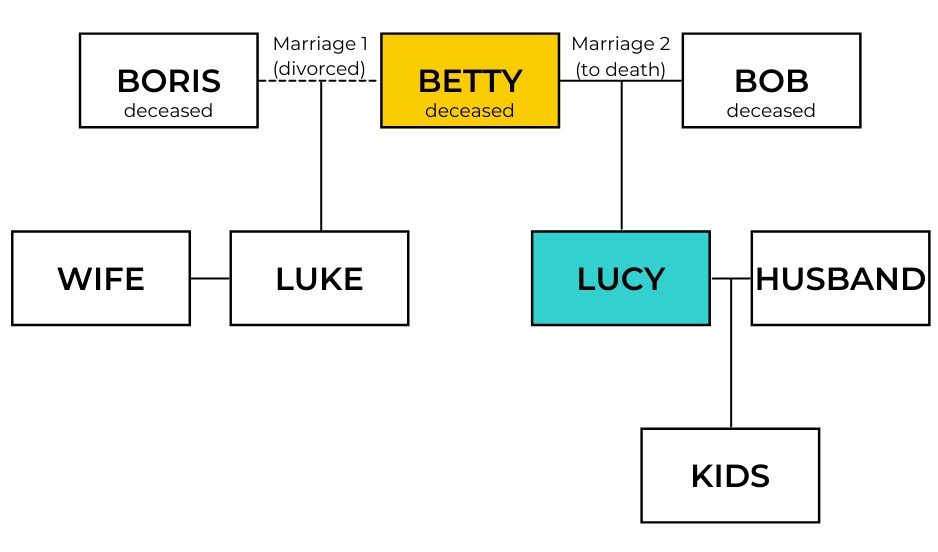

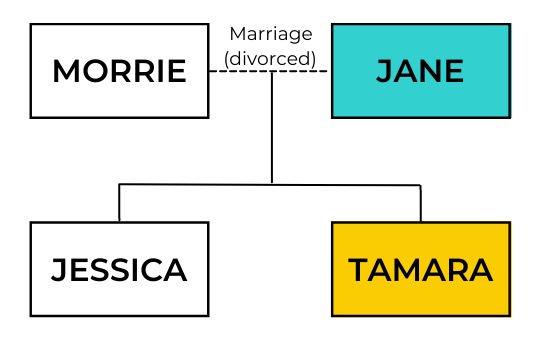

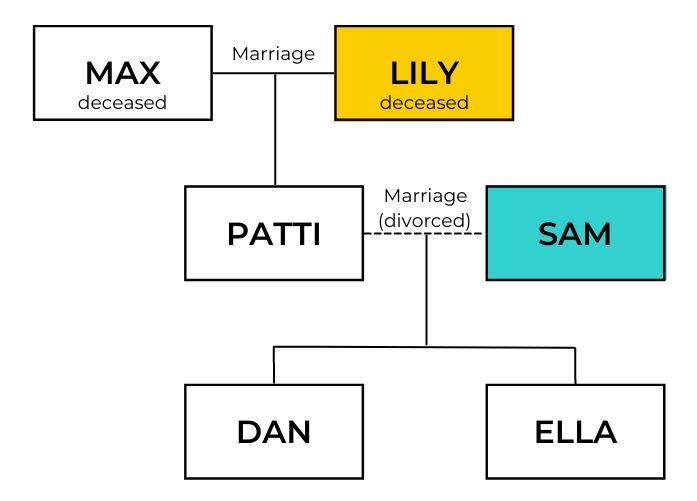

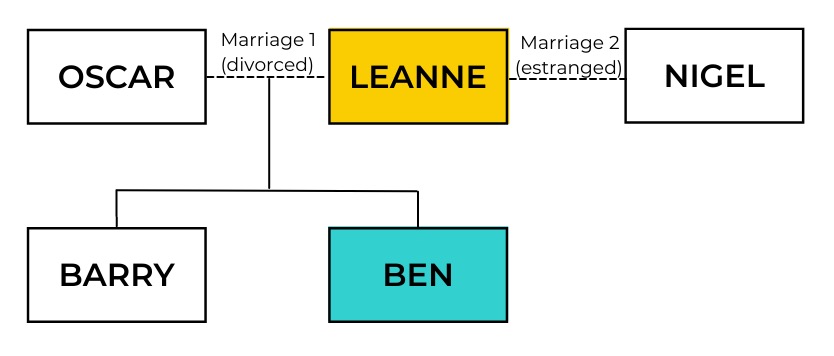

I’ve included a family tree for each story, to help clarify relationships. The person whose story is being told is in blue. The person whose estate was involved is in yellow.

There are, of course, many sides to every story. I’ve tried to stick to the pertinent facts only and have thoroughly tested them, including asking to see various documents. Everything contained here is backed up by evidence.

But we’ll never know the full story of any of this, so let’s not judge anyone too harshly, OK?

Let’s start with Lucy…

Lucy’s story: A lack of trust between siblings

Lucy’s father Bob was born in WW1 England, and his marriage to Betty was traditional: he worked and managed all the money; she was mostly a housewife. Lucy’s memory is that Bob treated his stepson, Luke, like his own child – but Bob outright adored Lucy. She was the apple of his eye.

Luke was 10 years older than Lucy, and after immigrating with the family to Australia, he soon married and has remained happily so ever since. That marriage took him out of the family home, and even further away from his half-sister when Luke and his wife eventually moved to another state, so Luke and Lucy weren’t as close as siblings of similar ages tend to be.

Sadly, Luke and his wife never had children, though they were desperately wanted. They focused on work and became wealthy enough to retire in their early 50s.

Lucy married and had children, then the marriage broke down. She became a single parent with only minimal support, so had to get by on a shoestring for many years. She lived a few hours drive away from her parents, so they couldn’t help with babysitting. It was a hard life, but she did her best.

In their 70s, Betty and Bob discussed their estate with Lucy. Bob wanted to leave everything to Lucy, as Luke was wealthy with no kids while she struggled to get by supporting hers. Lucy argued that was unfair and that Luke should get some too. Lucy suggested splitting the estate in equal parts between Lucy, Luke and the grandkids. Betty wrote a letter to Lucy, naming her executor and asking her to do what she thought best. In it, Betty acknowledged it was a weighty role, but that Betty and Bob knew Lucy was up to it and had full faith in her abilities.

Although they hadn’t specified where the money should go, Lucy intended to follow the equal parts split, per the discussion she’d had with her parents.

Years went by, then Bob died suddenly.

Bob’s death revealed how heavily Betty had been relying on Bob to remain at home. Cataracts had left her nearly blind, and doctors were loath to operate due to her age.

After an unfruitful search for a suitable nursing home, Lucy moved Betty into a spare room in Lucy’s home. Luke and Lucy agreed that was preferred versus Betty going to live with Luke. Lucy was still raising children and working full time, so it was not without its challenges – but Lucy loved her mum and made sure she was well cared for.

After a year of housing and caring for Betty, Lucy went on holidays for two weeks, arranging substitute care. While Lucy was away, Betty ended up in hospital. Primary cancer was found in her lung – thanks to 70 years of a pack-a-day habit – and secondary masses were blocking her bowel. Palliative options were the only ones offered.

Turning point

Without consulting Lucy, Luke and his wife flew Betty back to their home. They cared for her in her final few weeks. While they were caring for her, Betty rewrote her will.

It’s important to note that Betty possibly felt some guilt about Luke’s circumstances, though that was never expressed to Lucy or written down anywhere. Luke had a tough childhood after Betty’s first marriage to Boris ended. Any conversation of depth with Luke exposed deep emotional scars.

It’s also not clear who instigated the will rewrite. Luke was not forthcoming with that information.

After Betty died, Luke presented Lucy – the executor – with a will from Betty that left a token amount to each of the grandchildren and split the bulk of the estate in half, between Lucy and Luke.

He would not listen to Lucy’s attempts to explain the discussions with Bob and Betty. He didn’t believe her assertion that Bob hadn’t wanted to leave Luke anything because of Lucy’s tenuous financial circumstances, and that Lucy had had to argue in Luke’s favour. Luke basically called Lucy a liar and told her to get on with following Betty’s will, all via written correspondence instead of a phone call or a visit.

Lucy didn’t want to go to court as the estate wasn’t large enough to warrant it, even though her financial need was greater than Luke’s and the court was more likely to find in her favour on that basis. She followed Betty’s final will.

Result

The half-siblings became estranged.

Lucy says it was shocking to realise her half-brother would treat her so callously and with so little trust. Lucy remains sad that Luke overrode Bob’s wishes and didn’t involve her in the rewriting of Betty’s will, choosing instead to present it after Betty’s death. She is still disappointed that he wouldn’t even listen to her, even though she was executor.

Of the two, Lucy judges Luke lost the most. He didn’t need the money, but taking it meant he missed out on the joy that nieces and nephews – and their children – can bring. His estrangement from his half-sister means he has not developed close relationships with any of them.

Jane’s story: The importance of binding death nominations and notarising wills

Tamara’s death in her mid 20’s was a shock to both Morrie and Jane. No one should have to bury their child. Morrie and Tamara were not close at the time, but that doesn’t soften the blow of losing her.

Jane and Morrie remained amicable through divorce and co-parenting. Jane even wrote off Morrie’s significant child support debt to help Morrie avoid bankruptcy a few years prior to Tamara’s death.

Tamara died with superannuation and life insurance amounting to $250,000. She had a non-binding nomination for Jane as her 100% beneficiary in the super fund. They found a signed will from Tamara in her records, again leaving everything to Jane, but it was not notarised (i.e. independently witnessed).

Turning point

Morrie decided to challenge the estate.

Following legal advice, Jane learned that because Morrie was in financial distress, he would likely receive at least some of the estate if the case went to court. Even a notarised will would have been up for challenge, especially as there were no dependents (a spouse or child) involved. The only way to prevent Morrie’s attempt to claim would have been a binding death nomination made by Tamara to the super fund.

Not wanting to chew up the estate in legal fees, Jane and Morrie reached a settlement: the lesser part to Morrie, the greater part to Jane. After tax – which is paid on death benefits going to non-dependents – that was around $70,000 and $120,000 respectively.

Result

Morrie gave his entire share to his girlfriend. The girlfriend thanked him for it by promptly ending their 10-year relationship and kicking him out.

It permanently affected his relationship with his remaining daughter, Jessica, who doesn’t trust Morrie as much as she once did.

It still irks Jane that Morrie’s now ex-girlfriend got Tamara’s money in the end. The girlfriend was unforgivably cruel to Tamara, and never apologised or attempted to make amends.

Sam’s story: Mum screws over kids

After having kids, Patti became a prescription painkiller addict. She stole money from her school-aged children’s savings accounts and generally treated them badly enough that they moved in permanently with their father, Sam.

Patti also became estranged from Max and Lily, and never reconciled before either of their deaths. Max went first. When Lily became terminally ill with cancer, she had the lawyers write her will in a specific way: Patti wasn’t to receive any part of the estate until she’d paid back her debt of some tens of thousands of dollars allegedly stolen from various family members.

In lieu of Patti receiving anything, the estate was to be split between Lily’s grandchildren, Dan and Ella. Because both kids were still young, Sam was to be custodian of the estate for them until they reached a specific age and could be responsible for the money themselves.

Turning point and result

Patti didn’t pay back those debts, so the executor followed Lily’s wishes. Patti contested this in court and got a settlement due to her financial circumstances. Sam was forced to sell Max and Lily’s family home, which he was living in with the kids, to meet Patti’s settlement.

Less than a year after that settlement, Patti died of the same cancer that killed Lily.

Ben’s story: The importance of binding death nominations #2

Nigel and Leanne married in their 60’s, a decade after they first got together. They were firmly de facto already, with joint assets and their own self-managed super fund (SMSF), but wanted the formality. It was also a spur-of-the-moment decision in that city famous for bogus, last-minute weddings: Las Vegas.

The marriage couldn’t be registered in Australia, so Leanne believed it wasn’t subject to Australia’s Marriage Act. She was wrong.

Throughout her relationship with Nigel, Leanne had maintained her son Ben would be her executor. She also maintained that her superannuation death benefit should be split between her sons, Ben and Barry.

Two months after the Las Vegas wedding, Leanne submitted a binding death nomination for Ben and Barry to receive 50% each of her death benefit as a lump sum. Every will before and after the wedding was consistent with that nomination. Leanne didn’t realise binding death nominations lapse after three years unless you specifically make them non-lapsing.

Leanne and Nigel’s relationship began to break down when Nigel decided to move interstate. While Leanne and Nigel took turns to visit each other sporadically, he began two affairs with two different women. Upon Leanne’s discovery of the second affair, Nigel came to stay with Leanne so they could give the relationship one last shot. One month later, they amicably separated and Nigel headed back interstate.

They already had separate homes and lives, and hadn’t supported each financially in years. They both went on to new relationships in their separate lives.

All that was left to do was begin splitting their joint assets, which they did. They decided to keep the SMSF intact because everything in it had always been treated separately – they each had their own accumulation and pension funds for example – and it would have been a lot of bother to unwind.

Then disaster struck. Leanne fell ill and died a year after her split from Nigel.

Ben became the executor of Leanne’s estate and Nigel became the trustee in charge of the SMSF.

Turning point

Nigel stated, on many occasions in email and on the phone to Ben, that he intended to honour Leanne’s wishes. Over time though, Nigel became obstructive. The reason soon became clear: he resolved to pay Leanne’s full death benefit to himself.

Dear reader, you might be wondering how this is even possible? So, a quick digression into SMSFs…

- In general, superannuation instructions override what’s in wills, and especially so with SMSFs.

- The terms of the deed of each SMSF are specific to that SMSF. In the deed for Leanne and Nigel’s SMSF, the fund allowed for Leanne’s first pension account to be paid to the surviving spouse. Leanne and Nigel never officially divorced, so they were estranged spouses at the time of death. As far as the law is concerned, that’s enough – unless their marriage can be proven invalid by other means.

- SMSF trustees are required by law to act in good faith, to use the funds for a proper purpose, and to take into account the best interests of potential beneficiaries. They must be unbiased and fair-minded in their decisions. They must ensure the fund is compliant with the law.

- Being a child or a spouse makes someone a dependent in superannuation terms, and therefore an automatic potential beneficiary.

- Regardless of all that, the trustee/s make the ultimate decision where the money goes and when, so long as they comply with the law and the trust deed. They’re supposed to follow a due process, but it’s essentially up to their discretion.

Nigel, Barry and Ben are all potential beneficiaries of Leanne’s death benefit. All are entitled to the proper administration of the SMSF, and Nigel has been solely responsible for that administration to date. It’s hard to see how Nigel could claim his decision is fair and unbiased.

Ben recently received advice that Nigel’s position is ‘vulnerable to litigation’. Ben also feels compelled to fight on Barry’s behalf, so he’s willing to gamble that the court will find in his and Barry’s favour.

Still, even if they lose in court, karma may yet intervene. Leanne left notes alleging Nigel engaged in tax practises that are contrary to the legislation. Perhaps the universe will send a tax audit Nigel’s way for ignoring her wishes.

It will be interesting to see how this case plays out! I’ll update this blog as things develop if Ben is willing.

The learnings

Lucy, Jane, Sam and Ben have kindly shared their stories, reliving all that trauma so we can all learn. Here’s what I’ve personally taken from their experiences:

Paperwork matters

If you want your will to be difficult to challenge, consider:

- A correctly written and notarised will. I strongly believe this should be done with a lawyer to reduce the chances of making an avoidable mistake. Mine is getting updated as a result of these experiences.

- A binding death nomination for your superannuation, whether it’s in a mainstream fund or your own SMSF. Remember, standard nominations lapse unless made specifically non-lapsing, so you need to renew every three years at the moment – this may change, and there’s a case waiting judgement that may affect this.

- Formalising divorces. Australia’s Marriage Act recognises most foreign marriages. Even if you’re married elsewhere, you must get divorced in Australia to make it official.

Recognise the true cost of challenging a will

Money aside, there’s irreparable damage caused to relationships and reputations in these processes. Siblings estranged, parent-child relationships tarnished, many future years of happy family memories thrown away for a few bucks.

But I reckon even that’s not the worst part.

The damage to one’s self-worth must be huge. Going against the will of a dead person is bad juju, and screwing others over to do it even more so. It’d be hard to claim moral rectitude, being a good role model or any kind of integrity with a straight face.

Personally, I pity the Lukes, Morries, Pattis and Nigels of the world. Making any decision that causes you to lose your self-respect is too costly in my opinion. The cognitive dissonance required to claim integrity while acting in the opposite must surely ruin your mental health.

Consider giving things away before you die

I’d like to encourage you to tell people what’s in your will so they know what to expect. That way, they can take up any beefs with you instead of taking them out on everyone else after you’ve died.

…but that’s a big ask, and wills do change. Threats to write someone out of the will can also be used as blackmail, so you might prefer to avoid open discussion.

If that’s the case, consider an alternative: giving specific gifts before you pass.

For example, while she was still alive, my beautiful great-aunt gave me my great-grandmother’s wedding ring and a bunch of photo albums.

I reckon estate contests are also the most persuasive argument for the ‘die with zero’ approach. Give it away before you go so there’s nothing left to fight over!

It’s still not persuasive enough for me to go that way, but it’s food for thought.

Set a limit on energy expended

Lawyers’ eyes light up when they meet the likes of Ben and Barry. They know they’ll get paid tens of thousands of dollars regardless of which way the case goes in litigation.

Not everyone is as willing as Ben and Barry to risk that money.

Taking the expedient route to mediate and settle outside court could be worth it if it saves you wasting enormous amounts of time and money chasing justice. Even walking away might be the right thing for you if fighting is too destructive elsewhere.

There’s no shame in it. You’re not to blame for the inadequacies of the law in practise, or poor decisions made by the deceased, or unethical ones made by those left behind. To borrow Blackstone’s ratio for criminal law’s basis:

‘It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.’

Estate law and criminal law may be worlds apart, but the same thing happens. Estates sometimes end up going to people it was never intended for, and who probably don’t deserve it – the ‘guilty’ in Blackstone’s ratio, if you like. Set yourself a mental limit for the amount of time and energy you’re willing to invest in the process. Ask people who love you to let you know when it’s time to give up and let go.

Aside: not all lawyers are created equal and remember to ask lots of questions

I’ll now add my personal experience to date being Fran’s executor (and I’m not done yet):

Legal terminology is confusing. For example, I’m used to the word ‘dependent’ in terms of welfare – a child is a ‘dependent’ while they live at home or under a certain age. In SMSF law, you’re a ‘dependent’ at any age and any living circumstance, because that refers to the parent-child relationship. So I’m Fran’s dependent, even though we lived separately and she didn’t financially support me.

If you don’t know what something means, ask for guidance until you do.

Secondly, lawyers are human (yes, really) and the law is complex. There are so many intricacies to navigate that unintentional errors in advice are possible. Lawyers are fallible and, just like all of us, they have their bad days too.

I hired a generalist firm in Queensland to help me administer Fran’s estate. Having now had specialist advice on one tricky bit, I realise a generalist approach is not necessarily sufficient for complex cases. Knowing when to pursue specialist advice is hard for a novice, but well worth it.

More importantly though, find someone who will communicate with you regularly and doesn’t leave your calls or emails ignored. The firm I used was appalling on that front. It took weeks – sometimes multiple months – to get email responses or a call back. The communication was woeful from the top down.

They’ve apologised profusely numerous times, promised to respond to all emails and calls within one business day… then gone straight back to slow responses, again and again.

This is my first experience with lawyers, so I didn’t realise this is not normal behaviour.

From this I have learned: if you are not happy with your lawyer, consider a change sooner rather than later. I really wish I’d kicked mine to the curb.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this read.

If you’ve got thoughts or experiences you’d like to share that are not confidential or defamatory, please feel free – this is a safe space to do so. Though please note you’re in my house and I reserve the right to block or delete anything offensive or potentially defamatory.

Also, please don’t speculate on who might be involved in these stories in the comments. It’s not fair on the people involved and you’re only hearing one side of each story.

Hi Lacey,

This was interesting reading. Unfortunately it is coloured by your strong prejudice against those who opt to initiate a claim against an estate. Sure, there are some unscrupulous people who will ‘screw others over for the sake of a few bucks’. Your words, not mine. But I’m disappointed you don’t allow space in your opinion for those who suddenly find themselves with nothing as a result of their long term spouse’s death, as per your paragraph on the origin of making wills. Poor decision making and wills that are not updated regularly should receive some of your scorn. Please reserve some judgement against those that have no choice.